tIn a November, 1999 article in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Burl Burlingame wrote, “Hawaiian culture, largely repressed at the beginning of the century in favor of Western education, began a comeback in the 1960’s and is in full flower today. The ‘Hawaiian Renaissance’ would have had trouble getting off the ground, however, if it had not been for the tools provided by educator Mary Kawena Pukui.

tIn a November, 1999 article in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Burl Burlingame wrote, “Hawaiian culture, largely repressed at the beginning of the century in favor of Western education, began a comeback in the 1960’s and is in full flower today. The ‘Hawaiian Renaissance’ would have had trouble getting off the ground, however, if it had not been for the tools provided by educator Mary Kawena Pukui.

In the August/September 2007 issue of Hana Hou! magazine, in an article entitled “Kawena’s Legacy” by Chad Blair, DeSoto Brown, Bishop Museum archivist said, “Kawena really is the primary informant for how the Hawaiian culture is practiced today. She recognized that the language and the knowledge were being lost. Kawena felt it incumbent on her to make sure Hawaiians who came after her would be able to go to her work and learn from it.” In the same article, Aunty Pat Namaka Bacon, Kawena’s hanai daughter added, “She always wanted to preserve whatever she had learned.”

The University of Hawai’i at Manoa’s Library guide states, “Mary Kawena Puku’i’s published work spans over 50 years, and her contributions to Hawaiian knowledge and preservation make her a giant in both the fields of Hawaiian language and Hawaiian studies. It is not much of a leap to say that were it not for Tutu Puku’i, much of the information and texts we take for granted would either have remained lost, or would have been trnslated much later. It is not too far-fetched to say that before her death, no other living Hawaiian had worked as hard to preserve the knowledge and culture of the Hawaiian people.”

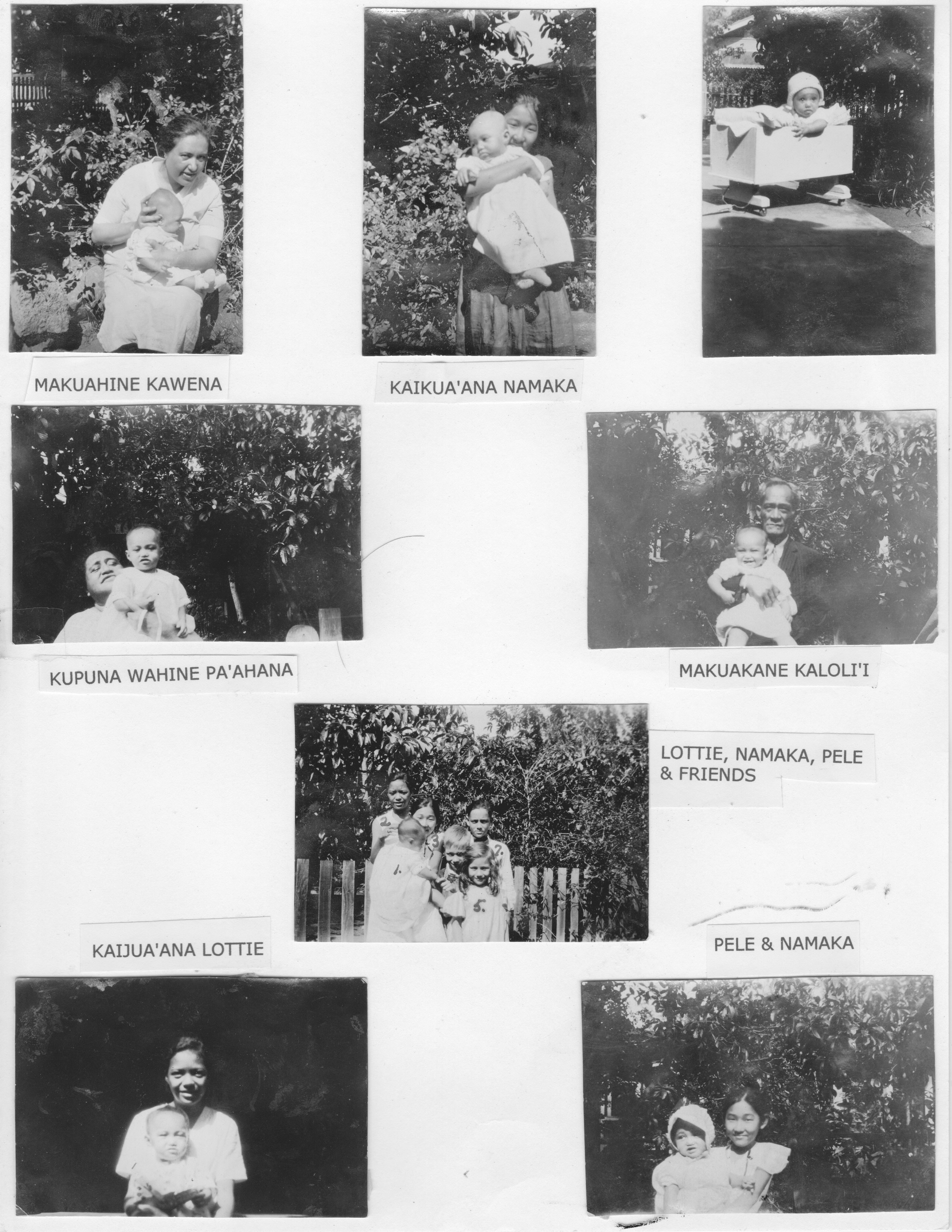

EARLY LIFE & ‘OHANA: It was about noon on Saturday, April 20, 1895, when Akoni Kawa’a met his brother-in-law, Henry Wiggin, about to stop at a coffee shop on his way home from work at the Hutchinson Sugar Co. in Na’alehu and said, “E Hale, he kaikamahine momona,” (Harry, it’s a fat girl). The new father turned his horse around and galloped toward his mother-in-law’s house, Hale Ola, at Haniumalu, above Na’alehu, Ka’u, on the island of Hawaii. The little infant was delivered by her grandmother, Nali’ipo’aimoku, an experienced midwife. She was named Mary Abigail Ka-wena-‘ula-o-ka-lani-a-Hi’iaka-i-ka-poli-o-Pele-ka-wahine-‘ai-honua (The rosy glow in the sky made by Hi’iaka who was raised in the bosom of Pele, the earth consuming woman) Na-lei-lehua-a-Pele (Pele’s lehua leis) Wiggin. [The next time you watch the sun descend into the ocean at sunset and enjoy the colors of the sky, the rosy glow you see is ka-wena-‘ula.] The last name given the child was in reference to Kawena and her deceased older sister, Mary Binning, from Pa’ahana’s previous marriage. Her name appropriately established her family’s ties to the fire goddess,Pele, and the fire clan of Ka’u, who claim direct descendency from Pele. To all Hawaiians, Pele is Akua (god/goddess) but to the people of Ka’u, Pele is also Aumakua (family guardian).

*******

To Hawaiians, names are very important and carefully given. One would never use just any name they may have heard or seen and many names tied one to family and ancestry and would be recognized. Also inoa po (night names) given by ancestors, aumākua or gods/goddesses in dreams, must be given a child lest the child face illness or death. Kawena’s first Hawaiian name was an inoa po and was told to her aunt, Mary Rebecca Pu’uheana, in a dream just before she was born. To use a name without the proper relationship was inappropriate and just not done. Neither was falsely claiming a familial relationship. To do so was at the very least, shameful, and could even be harmful, should there be a kapu on the name.

He pili nakeke.

A relationship that fits so loosely that it rattles.

Names, like Na-li’i-po’ai-moku’s were commemorative, remembering a trip around Hawai’i island by two Ka’u chiefs who were cousins and brothers-in-law, Hinawale and OwalawahieaKaumaka. They were Po’ai’s great grandfather and great granduncle, respectively. OwalawahieaKaumaka was the paternal uncle of the beloved Ka’u chief, Kupake’e.

Another form of naming was inoa kuamuamu. If someone heard an insult directed at a loved one or relative, the insult would live in a name as a sign of contempt, so the offender would be reminded whenever the name was heard. This is an ancient Hawaiian practice and not easily understood, except by the older generations of Hawaiians. For example, Kawena’s mother heard someone say that her daughter had “haughty” eyes. One of Kawena’s hanai daughters was named Na-maka-uahoa-o- Kawena-‘ula-o-ka-lani (The haughty eyes of Kawena ‘ulaokalani). When this child suffered severely from sickness, Pa ‘ahana had a dream, inoa po, to add to her name, ikiiki-o-ka-lani-nui, to proclaim her a member of the Ka ‘u clan protected by Pele. When this addition was voiced by Pa ‘ahana, her illnesses disappeared. Another example of inoa kuamuamu being used was by Kawena’s great grandfather, Mokila. He was the head kahuna kalai wa‛a (canoe making expert), cousin and constant companion of the chief, Lilikalani aka Haililani. Whenever he heard of an unkind word directed at Haililani, he named his sons accordingly. The first was named Ke-li‛i-kanaka-‛ole-o-Haililani (Haililani, the chief without servants), then Ke-li‛i-kahakā-o-Haililani (Haililani, the disagreeable chief), then Ke-li‛i-kipi-o-Haililani (Haililani, the traitor chief) and Ke-li‛i-pio-o-Haililani (Haililani, the captive chief). When the eldest son died, without any offspring, his brother, Ke-li‛i-kahakā-o-Haililani, took his older, deceased brother’s name, so it would live on, and went by Kanaka’ole. He was Kawena’s grandfather, whose wives were Pamaho‛a, aka Kuku‘ena-i-ka-ahi-ho‘omau-honua, then her cousin, Nali‛ipo‛aimoku, with their children being his descendents. There are no others.. There is also another form of kuamuamu which involves giving a newborn child such a vile and repulsive name, that evil spirits, who would otherwise snatch the life from the baby, would leave the babyalone

* * * I M P O R T A N T N O T I C E * *

As stated above, when the elder brother died (he had no children), his younger brother adopted his name, Keli’ikanaka’ole-o=Haililani, so it would live on. It has been brought to our attention that there are people who are using this name and claim to be descendants. Please (be aware that the only descendants of this brother today are those from Mary Pu’uheana KawahinepelekaneoLunalilo (Kanaka’ole), Fannie Sarah Kamakolunuiokalani Kaulaokeahi (Kanaka’ole), Mary Catherine Keli’ipa’ahana Hi’ileilani Hi’iakaikawaiola (Kanaka’ole) and Rose Angeline Ka’iakoiliokalani Kaliko’iliahiokalani (Kanaka’ole) who were Kanaka’ole’s children with Nali’ipo’aimoku, as well as Ka’iā (Kanaka’ole) and Kukuena (Kanaka’ole) who were Kanaka’ole’s children with Pamaho’a. THERE ARE NO OTHERS!

Some years back, noted genealogist, Edith McKenzie, took Edith and Luka Kanaka’ole to meet with Mary Kawena Pūku’i at her Manoa home to discuss genealogy.* These revered kūpuna talked for a long time, determined and agreed that there was no relationship between our two families! Any claim to the contrary today would demonstrate utter disregard for the knowledge of these respected kūpuna, while exhibiting shameful and very un-Hawaiian behavior.

In addition, knowingly making false claims for gain can be prosecuted in court. But, most importantly, this kind of activity is not the way of our people and can only cause unnecessary confusion, arguments and perhaps resentment. As Hawaiians, we must respect our kupuna and elders, as we have been taught and must teach our children to do.

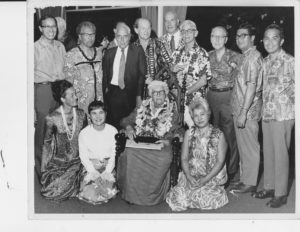

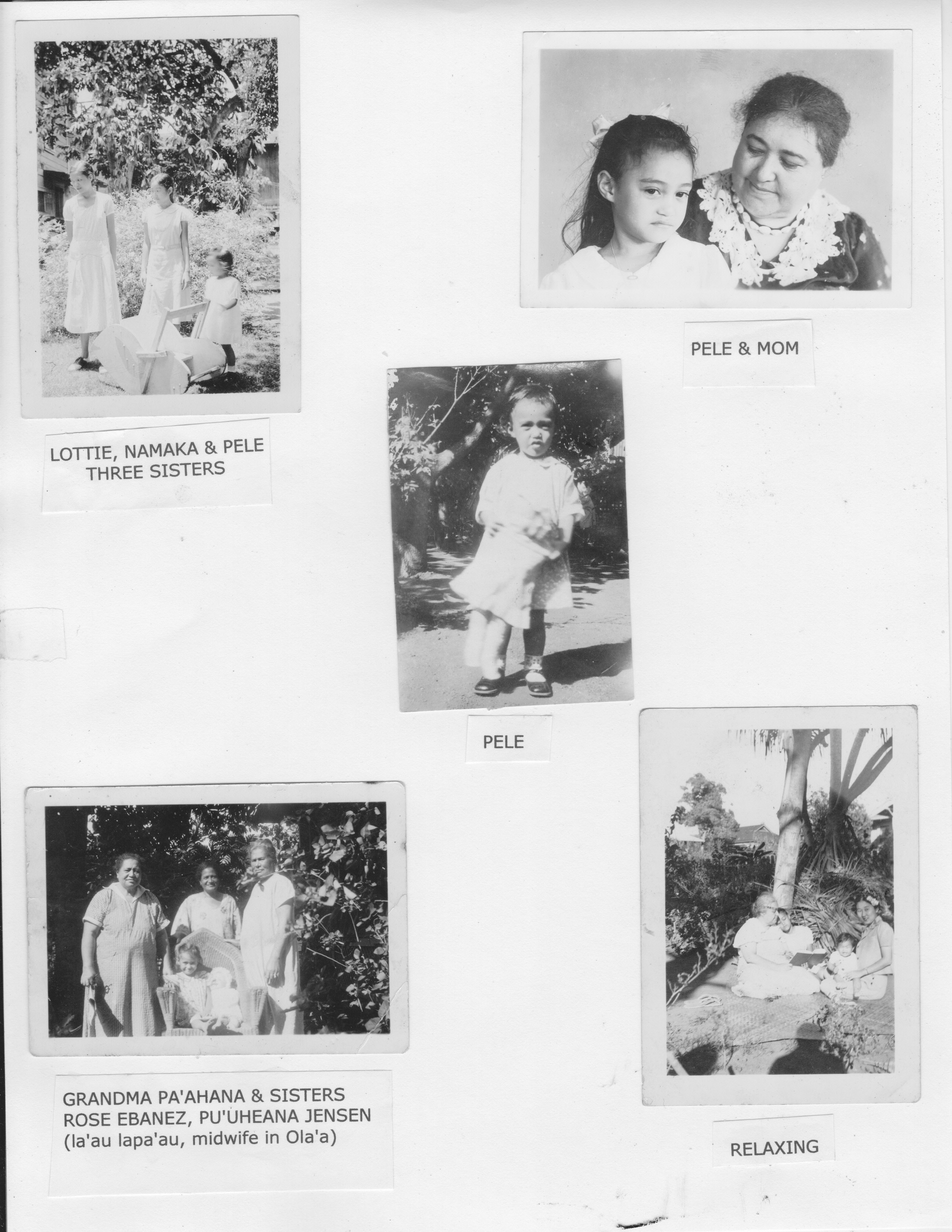

*(Kawena and Edith were not strangers. Kawena’s daughter, Pele, died of a heart attack after chanting for Edith, who was receiving an award from Gov. George Ariyoshi at the capitol. The last picture of Pele is of her chanting for Edith and holding her hand, with Luka behind them. Edith went to Manoa and spent the evening with Kawena.)

[This notice is because of inquiries and confusion. We hope this will put this matter to rest.]

********

As her father entered the bedroom where the new baby lay, he said, “Hello Tui.” That was the name he called her from that moment until his last breath. Her mother was Mary Pa’ahana Kanaka’ole of Ka’u and her father, Henry Nathaniel Wiggin from Salem, Massachusetts. As the two new parents sat and gazed upon the newborn infant, something occurred that would set the tone for this child’s entire life. You see, it was an old Hawaiian custom that the first born child was given to the grandparents to be reared and taught; a boy to his paternal grandparents and a girl to her maternal grandparents. It was then the responsibility of the grandparents to teach their mo’opuna the family history, genealogy, traditions, legends, who their aumakua were, the lore and language of their people, etc. It was an ancient custom that bore much responsibility for both kupuna (grandparent) and child. The infant’s grandmother went and sat at her haole son-in-law’s feet and looked up at his face. She hesitated to ask him the same question she had asked her Hawaiian sons-in-law each time there was a birth of a baby girl, as she had been turned down each time and told, “He au hou keia!” (This is a new era with new ways!) Although she had been disappointed in the past, she was driven by her traditional family duty. She quietly asked her haole son-in-law, “E Hale, na’u ka mo’opuna?” (Harry, is the grandchild mine?) Kawena’s father, who had much respect and aloha for his Hawaiian mother-in-law, gently touched her shoulder and responded, “Ae, Mama, nāu no ka mo’opuna.” (Yes, Mama, she is yours). Po’ai sat quietly, then stood and went to tell her eldest daughter, Mary Rebecca Pu’uheana, that the baby born that day was hers to raise.

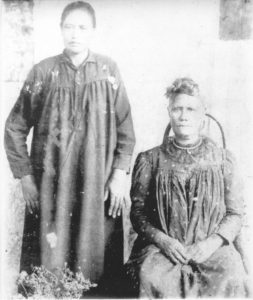

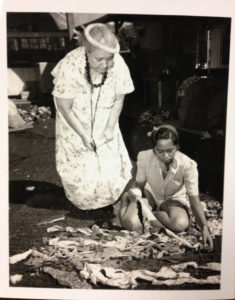

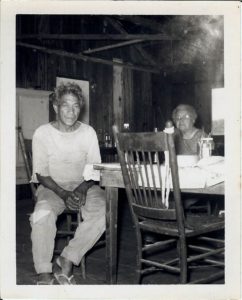

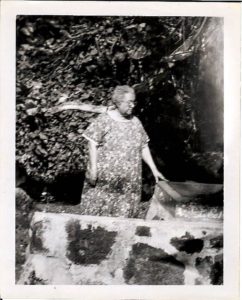

NALI’IPO’AIMOKU (standing) and KALIMAKUHILANI, HER AUNT AND TWIN SISTER OF HER MOTHER, KELI‛IPA‛AHANA Pa’ahana was surprised at this and asked her husband why he did that. “Your mama is getting old,” he said, “and doesn’t have too many years left. Let them be happy ones with a grandchild to teach and to raise in the Hawaiian manner.” From that day until Po’ai breathed her last and left this life, the two were inseparable. Kawena’s father, Henry Nathaniel Wiggin, was a New Englander from Salem, Massachusetts, who came to Hawai‘i in 1892 to work at the Hutchinson plantation in Na‘alehu, Ka‘ū, as head luna. His New England family had owned ships and forests for timber. He spoke fluent Hawaiian but only spoke English to his daughter. He was a direct descendent of America’s first poet, Anne Bradstreet and Massachussets Bay Colony governors, Thomas Dudley (who signed the charter for Harvard University at Cambridge), and Simon Bradstreet. He introduced to herstories of Paul Revere, Ichabod Crane and Rip Van Winkle; the poetry ofHenry Wadsworth Longfellow; read from Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Bible, exposing her to his language and New England heritage. This knowledge of her mother’s, as well as her father’s language was invaluable and allowed her to bridge the two. It was an old Hawaiian custom that the ‘iēwe (placenta) of a newborn be buried under a tree or rock. Because of her mixture of Hawaiian and foreign ancestry, Kawena’s grandmother buried hers under a loquat tree, one of two foreign trees that grew there. The other foreign tree, a avocado, was where older sister’s ‘iēwe, from an earlier marriage and who died in infancy, was buried. After a month at Hale Ola, Kawena and her parents returned to their home in Na’alehu. Her grandmother gathered what she needed and went, too. At three months old, Po’ai added pa’i ‘uala (compressed sweet potato used as a substitute for poi, also called poi ‘uala) to the baby’s diet made from ‘uala (sweet potato) from Po’ai’s garden. If the baby needed a mild laxative, Po’ai would squeeze the juice from ‘ilima blossoms gathered from her garden into Kawena’s mouth. (This is called kanaka maika’i) A broth from ‘opihi (limpet) was fed for strength. Also, as was custom, nine days after the umbilical cord (piko) dropped off, it was taken to Pa’ula cave and secreted there. Many generations of Ka’u families had their piko hidden there. Po’ai also shaped the baby’s body to make the body attractive; a very old Hawaiian practicd. There was a desired look, accomplished by the shaping of the head, especially within the ali’i class. Infancy was the time to perfect the features of a favorite child. Long, tapered fingers were preferred over short, stubby ones, so they were pulled with the tips gently rolled to make them taper. A flat nose (‘upepe) was pressed for a sharper ridge, the buttocks, especially of a boy, should be round and not flat (kikala pai). Mothers were careful not to let the child’s ears fold over, lest they stick out; eyes would be pressed from the sides to make them larger, heads were gently shaped for a pleasing appearance. A flat head (po’o ‘opaha) was unattractive so babies must not be laid only on the back. This is a very old Hawaiian practice and Po’ai applied her knowledge on her baby. When Kawena was seven or eight months old, she fell off of her parents’ bed, where her father had laid her, and injured her back. Po’ai massaged Kawena daily with the juice of mashed raw kukui nuts. In addition, she buried her little one up to her waist in sand and stood behind Kawena with her arms through her baby’s armpits and very gently lifted her. She continued this, with her massaging, for several years, until Kawena was healed. This type of corrective treatment was called pakolea. When Kawena was eleven months old, her weaning took place at her grandmother’s home. Po’ai said prayers to Ku and Hina to remove the baby’s desire for breast milk. Kawena sat on her grandmother’s lap while two small stones were placed in front of her, The stones represented her mother’s breasts. Her mother, Pa’ahana, answered questions posed by Po’ai, acting as proxy for her daughter. There were questions, such as, “Do you wish the desire for breast milk to go away?” When all the questions were answered, Kawena picked up one of the stones and threw it off the lanai, signifying no further interest in breast-feeding. The stone hit her aunt, Mary Rebecca Pu’uheana, who lived there with her husband, Akoni Kawa’a, on the back between her shoulders. Thus ended the weaning process. Pa’ahana returned to their home in Na’alehu and Kawena stayed at Hale Ola with her grandmother. .Kawena’s older sister, Mary Binning, who was from Pa‘ahana’s previous marriage and who had died in infancy, was the hiapo (first born) and for her was held the ‘Aha‘aina Mawaewae, the last one held in the family.

NALI’IPO’AIMOKU (standing) and KALIMAKUHILANI, HER AUNT AND TWIN SISTER OF HER MOTHER, KELI‛IPA‛AHANA Pa’ahana was surprised at this and asked her husband why he did that. “Your mama is getting old,” he said, “and doesn’t have too many years left. Let them be happy ones with a grandchild to teach and to raise in the Hawaiian manner.” From that day until Po’ai breathed her last and left this life, the two were inseparable. Kawena’s father, Henry Nathaniel Wiggin, was a New Englander from Salem, Massachusetts, who came to Hawai‘i in 1892 to work at the Hutchinson plantation in Na‘alehu, Ka‘ū, as head luna. His New England family had owned ships and forests for timber. He spoke fluent Hawaiian but only spoke English to his daughter. He was a direct descendent of America’s first poet, Anne Bradstreet and Massachussets Bay Colony governors, Thomas Dudley (who signed the charter for Harvard University at Cambridge), and Simon Bradstreet. He introduced to herstories of Paul Revere, Ichabod Crane and Rip Van Winkle; the poetry ofHenry Wadsworth Longfellow; read from Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Bible, exposing her to his language and New England heritage. This knowledge of her mother’s, as well as her father’s language was invaluable and allowed her to bridge the two. It was an old Hawaiian custom that the ‘iēwe (placenta) of a newborn be buried under a tree or rock. Because of her mixture of Hawaiian and foreign ancestry, Kawena’s grandmother buried hers under a loquat tree, one of two foreign trees that grew there. The other foreign tree, a avocado, was where older sister’s ‘iēwe, from an earlier marriage and who died in infancy, was buried. After a month at Hale Ola, Kawena and her parents returned to their home in Na’alehu. Her grandmother gathered what she needed and went, too. At three months old, Po’ai added pa’i ‘uala (compressed sweet potato used as a substitute for poi, also called poi ‘uala) to the baby’s diet made from ‘uala (sweet potato) from Po’ai’s garden. If the baby needed a mild laxative, Po’ai would squeeze the juice from ‘ilima blossoms gathered from her garden into Kawena’s mouth. (This is called kanaka maika’i) A broth from ‘opihi (limpet) was fed for strength. Also, as was custom, nine days after the umbilical cord (piko) dropped off, it was taken to Pa’ula cave and secreted there. Many generations of Ka’u families had their piko hidden there. Po’ai also shaped the baby’s body to make the body attractive; a very old Hawaiian practicd. There was a desired look, accomplished by the shaping of the head, especially within the ali’i class. Infancy was the time to perfect the features of a favorite child. Long, tapered fingers were preferred over short, stubby ones, so they were pulled with the tips gently rolled to make them taper. A flat nose (‘upepe) was pressed for a sharper ridge, the buttocks, especially of a boy, should be round and not flat (kikala pai). Mothers were careful not to let the child’s ears fold over, lest they stick out; eyes would be pressed from the sides to make them larger, heads were gently shaped for a pleasing appearance. A flat head (po’o ‘opaha) was unattractive so babies must not be laid only on the back. This is a very old Hawaiian practice and Po’ai applied her knowledge on her baby. When Kawena was seven or eight months old, she fell off of her parents’ bed, where her father had laid her, and injured her back. Po’ai massaged Kawena daily with the juice of mashed raw kukui nuts. In addition, she buried her little one up to her waist in sand and stood behind Kawena with her arms through her baby’s armpits and very gently lifted her. She continued this, with her massaging, for several years, until Kawena was healed. This type of corrective treatment was called pakolea. When Kawena was eleven months old, her weaning took place at her grandmother’s home. Po’ai said prayers to Ku and Hina to remove the baby’s desire for breast milk. Kawena sat on her grandmother’s lap while two small stones were placed in front of her, The stones represented her mother’s breasts. Her mother, Pa’ahana, answered questions posed by Po’ai, acting as proxy for her daughter. There were questions, such as, “Do you wish the desire for breast milk to go away?” When all the questions were answered, Kawena picked up one of the stones and threw it off the lanai, signifying no further interest in breast-feeding. The stone hit her aunt, Mary Rebecca Pu’uheana, who lived there with her husband, Akoni Kawa’a, on the back between her shoulders. Thus ended the weaning process. Pa’ahana returned to their home in Na’alehu and Kawena stayed at Hale Ola with her grandmother. .Kawena’s older sister, Mary Binning, who was from Pa‘ahana’s previous marriage and who had died in infancy, was the hiapo (first born) and for her was held the ‘Aha‘aina Mawaewae, the last one held in the family.

The following is a kanikau, a lamentation written for Mary Binning by her mother, Pa‘ahana:

He kanikau, he aloha kēia,

Nou no e Miss Mary Binning,

Ku‘u Kaikamahine i ka makani kuehu lepo o Na‘alehu,

Aloha kahi a kaua e noho ai ,

‘Auwe ku‘u kaikamahine ho‘i e,

Ku‘u kaikamahine i ka pali o Lauhu,

E hu‘e pau mai ana ko aloha i ku‘u waimaka,

‘Auwe ku‘u kaikamahine, ku‘u aloha la e—

Ku‘u kaikamahine i ka wai hu‘i o Ka-puna,

Aloha ia wahi a kaua e hele ai

Ku‘u kaikamahine i ka ua nihi pali o Ha‘ao,

Aloha ia wahi a kaua e pili ai,

Pi‘i aku kaua o ke ala loa,

O ke alanui malihini makamaka‘ole,

‘Auwe ku‘u aloha ku‘u minamina e

Ua hele i ke ala ho‘i ‘ole mai

Auwe ku‘u lei, ku‘u milimili la e,

Ku‘u hoa pili o ua ‘aina nei,

Eia au ke noho a‘e nei,

Me ka ukana nui he aloha.

‘Auwe kuēu lei momi la e

Kuēu kaikamahine i ka wela o Wai-ka-puna

Aloha ia wahi a kaua e hele ai,

Ku‘u kaikamahine i ke ‘ala o na pua,

‘Auwe ku‘u lei kula e, aloha no, a…

This is a dirge, an expression of affection,

For you, O Miss Mary Binning,

My daughter in the dust-scattering wind of Na‘alehu,

In the home we shared together,

Oh——-my daughter!

My daughter at the cliff of Lau-hu

Love for you makes my tears flow unchecked,

Oh my daughter at the cold spring of Ka-puna,

A beloved place to which we went,

My daughter in the rain that passes the hill of Ha‘ao,

A place we were fond of going together,

We used to go up the long trail,

A little known trail, unattended by a friend,

Oh my darling –how sad i am at losing you,

You have gone on a road on which there is no returning,

Oh my darling–my pet,

My constant companion in the homeland,

Here I remain.

With this great load, a yearning for you,

Oh my darling, precious as a necklace of pearls,

My daughter in the warm sun of Waikapuna,

Beloved is that place where we used to go,

My daughter among the fragrant flowers,

Oh my necklace, my golden chain, farewell–alas–!

*****************

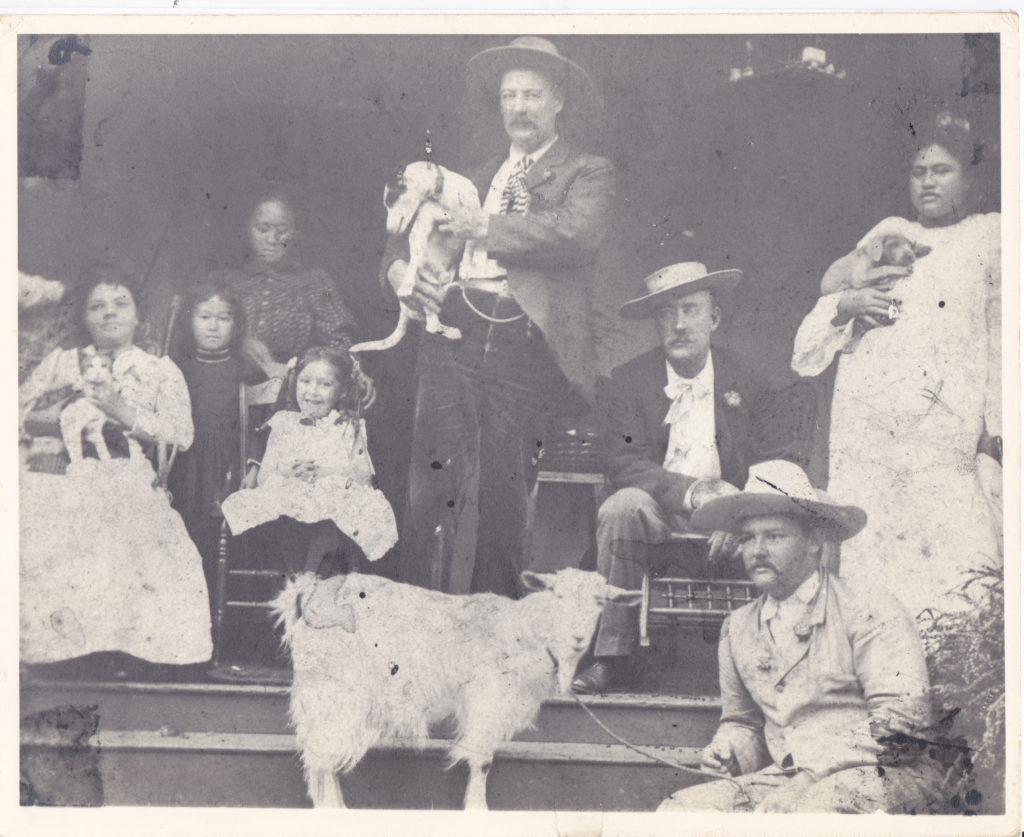

For Kawena’s first birthday, a ‘aha‘aina palala, usually given for the high chiefs and wealthy, was held. It was the largest feast held in her honor. Her parents raised the pigs and chickens; her uncles caught the fish and gathered the sea foods and her aunts did all the preparation, waited on the tables and cleaned up afterwards. Kawena’s father told her it was a very big affair. Being raised by her grandmother provided Kawena with a unique education and appreciation for her maternal heritage. Po‘ai taught Kawena the mother tongue of Hawai‘i, she memorized ancient chants and rituals, learned old hula, customs, beliefs, religion and family history. This Hawaiian custom of grandparents teaching the eldest of each family was to insure the preservation of the culture and lifestyle. Little Kawena was very curious about everything and was always asking questions of her grandmother. Once, when her grandmother was treating a woman in a closed room, Kawena was so curious that she climbed a tree and observed the proceedings quietly through a window, unbeknownst to anyone. Po’ai, an expert kahuna la’au lapa’au tended to all Kawena’s ailments, but she would defer to the plantation doctor, Dr. Thompson when faced with ma’i haole (foreign diseases) like mumps, measles, chicken pox, tracoma and others which she was never trained to treat. Tracoma had spread throughout the plantation and there was a shortage of help, so Harry would go into the camps himself, to drop medicine into the eyes of the laborers, resulting in him contracting the disease and losing the sight of one eye. Even though Kawena was kept away from contamination, she caught the disease anyway and almost lost the sight of both eyes. Dr. Thompson kept the room dark and her eyes bandaged for a couple of weeks. He visited his little patient daily, sometime spending an hour or so, telling her interesting things he saw or did. Kawena recovered and the family held a feast to give thanks. Kawena always remembered her doctor with affection for his care and attention paid to his little patienr.  WIGGIN ‘OHANAL to R: Abigail Wiggin, wife of Edwin Wiggin; Maggie Makino, friend; Ida the maid; Mary Abigail Kawena Wiggin; Edwin Wiggin, brother of Henry; Henry Nathaniel Wiggin, Kawena’s father; Mary Pa’ahana Wiggin, wife of Henry & mother of Kawena Front: Nancy, the favorite goat; Walter Hazelden, friend

WIGGIN ‘OHANAL to R: Abigail Wiggin, wife of Edwin Wiggin; Maggie Makino, friend; Ida the maid; Mary Abigail Kawena Wiggin; Edwin Wiggin, brother of Henry; Henry Nathaniel Wiggin, Kawena’s father; Mary Pa’ahana Wiggin, wife of Henry & mother of Kawena Front: Nancy, the favorite goat; Walter Hazelden, friend

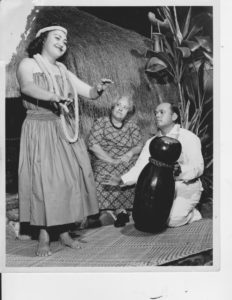

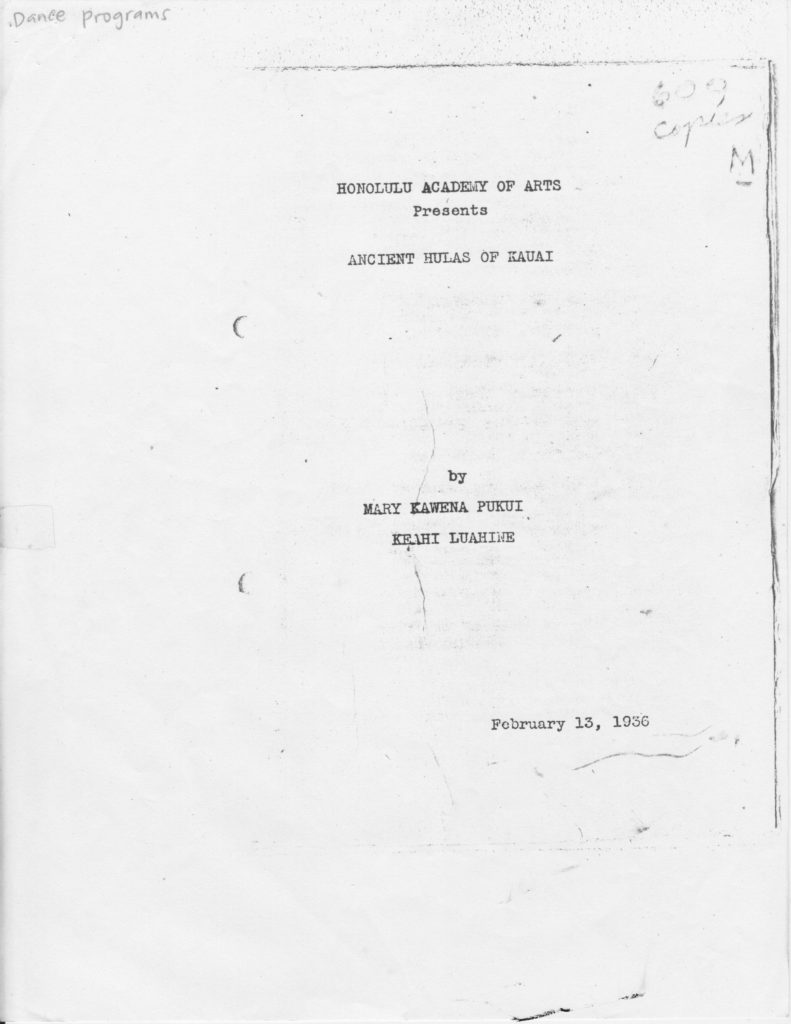

Po‘ai descended from a long line of kahuna, chiefs and chiefesses of Ka‘ū, and other districts, as well as Maui Island. She was very close to “her Queen Emma,” and was once summoned by the Queen to travel with her to Ni‘ihau, Kaua‘i and Ka‘ula as a dancer and chanter.  QUEEN EMMA Po‘ai, then in her late twenties, responded, meeting the queen in Honolulu, with her twenty year old cousin, Kuluwaimaka. (Kuluwaimaka is the great great grandfather of noted chanter/kumu hula, genealogist, lecturer and cultural expert, constantly called upon to judge hula competitions here and abroad, Cy Bridges, board member of the MKPCPS.)

QUEEN EMMA Po‘ai, then in her late twenties, responded, meeting the queen in Honolulu, with her twenty year old cousin, Kuluwaimaka. (Kuluwaimaka is the great great grandfather of noted chanter/kumu hula, genealogist, lecturer and cultural expert, constantly called upon to judge hula competitions here and abroad, Cy Bridges, board member of the MKPCPS.)  KULUWAIMAKA He was a noted chanter and in his late years became the chanter of Lalani Village in Waikiki. Po‘ai had recently given birth to a daughter, Kalamanamana, who she gave to her cousin, Ka-pule-nui, who lived in Manoa Valley and who had begged for a child of hers for so long, as he and his wife were childless. This allowed her to join her queen. Joining them in Honolulu were two teenaged sisters, ‘Ai ‘ō-nui and Ka-maka-huki-lani. They were relatives as they shared the same ancestry as the two from Ka’u. ‘Ai’ō-nui (Great debt) was named for the debt of the chief, Boki, and Ka-maka-huki-lani, for Boki’s mother. The ho’opa’a (drummer) for the group was a wahine named Keahi, who Kuluwaimaka later married. She was twice his age, very knowledgeable and expanded Kuluwaimaka’s repertoire. He descended from the chief, Palea, and was named for the tears shed by the chief, La’anui, of Ka’ū, when his beloved daughter passed away. After the tour, Po’ai returned to her family in Ka’u. Po‘ai had much aloha for “her” queen, Emma, and because of that deep aloha chose to have Kawena baptized by Bishop Willis of the Episcopalian church when he visited Ka‘ū. Queen Emma and her husband, Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho, were instrumental in the establishment of the Episcopal Church in Hawaii, founding St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Saint Andrew’s Priory School for Girls and laid the groundwork for Iolani School, named in honor of her husband.

KULUWAIMAKA He was a noted chanter and in his late years became the chanter of Lalani Village in Waikiki. Po‘ai had recently given birth to a daughter, Kalamanamana, who she gave to her cousin, Ka-pule-nui, who lived in Manoa Valley and who had begged for a child of hers for so long, as he and his wife were childless. This allowed her to join her queen. Joining them in Honolulu were two teenaged sisters, ‘Ai ‘ō-nui and Ka-maka-huki-lani. They were relatives as they shared the same ancestry as the two from Ka’u. ‘Ai’ō-nui (Great debt) was named for the debt of the chief, Boki, and Ka-maka-huki-lani, for Boki’s mother. The ho’opa’a (drummer) for the group was a wahine named Keahi, who Kuluwaimaka later married. She was twice his age, very knowledgeable and expanded Kuluwaimaka’s repertoire. He descended from the chief, Palea, and was named for the tears shed by the chief, La’anui, of Ka’ū, when his beloved daughter passed away. After the tour, Po’ai returned to her family in Ka’u. Po‘ai had much aloha for “her” queen, Emma, and because of that deep aloha chose to have Kawena baptized by Bishop Willis of the Episcopalian church when he visited Ka‘ū. Queen Emma and her husband, Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho, were instrumental in the establishment of the Episcopal Church in Hawaii, founding St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Saint Andrew’s Priory School for Girls and laid the groundwork for Iolani School, named in honor of her husband.

*********

Kawena’s godfather was a young Haole clerk who worked in the plantation store. His name was Alexander Lindsey, who, years later, became a judge in Honolulu. Po‘ai was named as godmother. Po‘ai’s knowledge was extensive and she passed on to her mo‘opuna punahele (favorite grandchild) everything she could. Po‘ai was a practiced midwife and expert in medicines, somtimes sending her young mo‘opuna out to gather the plants she needed. Little Kawena had been taught which hand to use to pick the medicinal plants and what prayer to utter while doing so. Po‘ai had learned to be a midwife from her mother, Ke-li‘i-pa‘ahana, who was an expert. Po‘ai trained three of her children: Ka‘iā, Ka-makolu-nui-o-ka-lani and Rebecca Pu‘u-heana. Po‘ai delivered alll her own children, except the last, Rose Ka‘iako’ili, when she needed Ka‘iā’s help at the last moment. Po‘ai would be up and working in one day. With mostly girls in her large family, Po‘ai had the younger ones do tasksusually done by boys. The two eldest girls, Mary Rebecca and Kamakolunuiokalani were taught to plait and sew. They were both very good, Mary Rebecca better at sewing and her younger sister wove a little better. A lauhala mat would be made in a single day. Mary Pa‘ahana was very good with children. She tended to the younger ones, helped with imu preparation, weed cutting/carrying and some cooking. Mary Rebecca, Rebecca Pu‘uheana and Rose were skilled in dressmaking. Mary Rebecca was the ‘ukeke player and Kawena loved to listen to her. When her foster mother put it down, Kawena would pick it up and mimic the sounds she heard and that’s how she learned to play the ancient instrument. As for playing the guitar, Mary Pa’ahana played slack key beautifully with her brother, Ke-li‘i-kipi-o-Haililani a close second. Mary Pa‘ahana and Kamakolu (who was named for one of Kalani‘ōpu‘u’s wives) were dancers, like their mother, and like Po‘ai, danced until the very last. The best singers were Mary Pa‘ahana and Annie Kukuena; the first had the sweeter voice and the latter, more husky with a memory for lyrics. Although Christianity was introduced to Hawai’i in 1820, ten years before Po‘ai was born, in 1830, she grew up only knowing the religion of her ancestors. Po‘ai had been raised by her step-father, Kanekuhia, who was a Priest of Lono and who taught her the chants and rituals of his calling. Her mother’s side of the family were ali’i, priests and priestesses of Pele and Kawena remembered watching her grandmother do some interesting dances. Po‘ai taught Kawena that respect was very important. Respect for the‘aumakua (family guardians), for the chiefs and one’s elders. She had to learn the names of her ‘aumakua so when there was a need, she could call on her own ‘aumakua instead of someone else’s. By the time she was five years old, Kawena had memorized the names of over fifty family ‘aumakua. ‘Aumakua were also called po‘e o ka pō (people of the night, or invisible people). However, they could take many visible forms, or kino lau, like shark, owl, lizard, bird, mouse, mudhen, eel, plant, rock, etc., as well as human form. An example is the story of one of Ku’s sons, Kumuhea, who settled at Pu‘u-‘enuhe (Caterpillar hill) in Ka‘ū, where he took a wife and only fed her his favorite diet of sweet potato leaves. She only saw him between sunset and sunrise and almost died from starvation. A kahuna discovered he was a supernatural being and her family appealed to his father, who took away his human form. Thereafter, he only had his other forms as a ‘enuhe (caterpillar) on land or loli (sea cucumber) in the sea. Kawena’s family would never kill a caterpillar or eat a sea cucumber. Kawena had to learn to understand signals given by ‘aumakua. For example, she learned if one’s pueo (owl) ‘aumakua behaved as though it wanted to be followed, do so because you’re being shown the safe path away from danger. If it crossed and re-crossed one’s path, there’s danger ahead so return from whence you came. If it slapped your shoulders, it means to sit down. The pueo will perch upon your head to disguise your presence. If slapped between the shoulder blades, one should lie down so the pueo can conceal one’s presence. Should the pueo cry at your doorway, it’s telling you to leave immediately because danger approaches. If the pueo takes one of your chickens, one must look within to determine what caused that to happen and to resolve the situation and the taking will stop.

******

‘AUMAKUA

(From Nānā I Ke Kumu vol.1)

There is a sea of time, so vast man cannot know its boundaries, so fathomless, man cannot plumb its depths. Into this dark sea plunge the spirits of men, released from their earthly bodies. The sea becomes one with the sky and the land and the fiery surging that rise from deep in the restless earth. For this is the measureless expanse of all space. This is the timelessness of all time. This is eternity. This is Pō. In Pō, there dwell our ancestors, transfigured into gods. They are forever god-spirits, possessing the strange and awesome powers of gods. Yet, they are forever our relatives, having for us the loving concern a mother feels for her infant, or a grandfather for his first-born grandson. As gods and relatives in one, they give us strength when we are weak, warning when danger threatens, guidance in our bewilderment, inspiration in our arts. They are equally our judges, hearing our words and watching our actions, reprimanding us for error, and punishing us for blatant offenses. For these are our godly ancestors. These are our spiritual parents. These are our ‘aumakua. You and I, when our time has come, shall plunge from our leina into Pō. If our lives have been worthy, our ‘aumakua will be waiting to welcome us. Then we too shall inhabit the eternal realm of the ancestor spirits. We, in our time, shall become ‘aumakua to our descendents even yet unborn.

******

THE SHARK GUARDIAN

(The following is a true story and took place when Kawena was a little girl in Ka‘ū. It first appeared in “Tales of the Menehune”; Mary K. Pūku‘i, C. Curtis; Bishop Museum Press; 1960.)

One very rainy day in Ka‘ū, little Kawena had a craving to eat nenue fish and told her mother what she wanted. Pa‘ahana told her they had none, couldn’t go fishing in the rain and to hush her nagging for nenue. She went into a corner and softly cried because she so wanted to eat nenue. Her aunt, Annie Kukuena dropped by to visit and asked Kawena what was wrong. “The sky is shedding enough tears,” she smiled and said to Kawena, “So why are you adding more?” Kawena whispered, “I really want nenue fish but we don’t have any.” The rain was now subsiding and her aunt said, “Then you and I shall get some. Let’s go see my uncle.” Kawena donned her raincoat and the two set off, talking, laughing and playing until they came to Tutu ‘Ōpū-Pele’s cave home, Puhi’ula by the beach. “Aloha,” said the old man, “What brings you two here on this rainy morning?” “The mo‘opuna is ‘ono for nenue,” said Kawena’s aunt. “Then nenue you shall have,” he said to Kawena. Tutu ‘Ōpū-Pele grabbed his net and climbed over his cave home to some rocks overlooking the bay. He stood motionless, after laying his net in the water, for a long time. Too long, thought Kawena as she stood quietly and watched, wondering why he didn’t do anything. All of a sudden she saw him move swiftly over the rocks to the beach, waded out into the water and gathered his net with fish in it. Kawena watched him as he held up one fish and threw it in the water and said, “The first one is for you, old one.” A shark rose up and seized the fish. Tutu ‘Ōpū-Pele said to the shark as he handed four nenue fish to Kawena, “These are for the mo‘opuna.” Kawena held her fish but watched in wonderment as the big shark swam away. They all stood and watched as the shark exited the bay, out into deep waters. “That is our guardian, our ‘aumakua,” said Tutu ‘Ōpū-Pele to the two standing next to him. “Tell our baby, Kawena, about our guardian,” said her aunt as the three walked back to the cave, “She ought to know that story.” After they sat comfortably in the cave, the old man began to tell the story. Many years ago, I found my older brother lying on the sand where we were standing a few minutes ago. I thought he was dead, but as I got closer, he opened his eyes and whispered something.. When I didn’t move, he said, “‘Awa and bananas……bring them quickly!” As I hurried to get what he wanted, I saw him pull himself up and, looking out to the bay, said, “The boy went to get ‘awa and bananas and will be right back.” He dragged himself to the rocks near where I stood earlier today and as I took what I had in my arms to him, he called out with all the strength he had, “Here is ‘awa. Here are bananas. Come and eat.” Suddenly, a large shark appeared. He opened his mouth and my brother poured ‘awa, followed by bananas that he peeled, until the shark was satisfied. My brother thanked the large one and said to come back anytime he’s hungry. As he swam away, my brother rested on the sand and told me what happened. He was out fishing by himself when he ran into a squall. His canoe overturned and the waves and heavy rain caused him to lose sight of the canoe. He was exhausted and believed his end was near, when he felt a rock and grabbed it. The rock started to move swiftly through the waves and he realized it was the dorsal fin of a great shark. He held on until the shark took him to the shore where I found him. My brother continued to feed the great one and catch the fish he would chase into my brother’s net. When he was breathing his last, he asked me to continue to take care of this guardian, which I have for many years. Today, he wanted to share nenue with you and put the thought into your mind, Kawena, so you would come and see him. We must never forget our guardian, our ‘aumakua. Kawena never forgot Pakaiea, the son of Kua, the great red shark, protector of Ka‘ū, and out of respect, our family does not wear red at the beach or in the ocean.

******

Kawena would relate in her later years that being in her position as a child, a punahele with many kapu, was sometimes difficult. It was also a little peculiar because she had older girl cousins who should have been the punahele, but their parents wouldn’t allow it. So, she was a junior, daughter of Po’ai’s 12th child, but Po’ai’s eldest daughter, Pu’uheana, lived with her mother and became Kawena’s foster. mother as there was much to learn and many restrictions; her food bowls, dishes and utensils were washed and kept separated; she had her own bathtub; her clothesline and pins were separate; her clothes were washed separately, could not be worn by anyone else and when outgrown, would be soaked and buried or burned; no one could rest on her sleeping mat nor eat out of her dishes. She was always around folks of her mother’s or grandmother’s generation. She could not be spanked, nor could her mother send her on errands. Except for her pet goat, Nancy, (who didn’t like males and would butt any male that came close to Kawena), she had no toys or playmates.

But she had her grandmother, Po‘ai. The two were inseparable. Wherever Po‘ai went, Kawena went too……to the beaches, to the upland, to the Mormon church at Nalua, to the wharf at Honu‘apo, spending the night at Palahemo in Kalae…..everywhere. When Po‘ai softened the earth around her potato mounds, the child was there, asking questions about the caterpillars, cocoons, rats’ nests or whatever she found. Po‘ai patiently answered all her mo‘opuna’s questions. There was much for Po‘ai to teach her mo‘opuna, things to do and things not to do. What to do if you’re alone and hear a whistle; what to do if you accidentally run into the huaka‘i i ka pō, the night marchers; what to do if the sea recedes suddenly, etc. Do not sit or stand near anyone with your hands on your hips, crossed behind your back or behind your head. Do not point a finger at the clouds or a rainbow lest you offend an ‘aumakua. Do not spit or make faces near anyone lest you become a victim of sorcery. Do not sit or stand in the doorway of the house. Do not run or play hide-and-seek in the house, do that outside. Do not deny food and/or water to anyone who asks, for it may be your ‘aumakua in human form. Do not interrupt an adult, but save any questions for later. Be still and quiet at story telling time. Kawena’s father had subscribed to a weekly Hawaiian newspaper for his mother-in-law and when it arrived, the neighbors joined Po‘ai and her family at Hale Ola and took turns reading aloud to the group. There was ‘Ōpū and his wife, Kapeka, also Ka-uwepa and his wife, La‘ie. Amongst this group sat little Kawena.

******

HAWAI’I……THE MOST LITERATE COUNTRY IN THE WORLD

(This article, written by La’akea Suganuma, was in the Jan/Feb 2004 issue of The ‘Oiwi Files newspaper) The fact is, Hawai‘i, at one time, was the most literate country in the entire world. Once our language became a written one, Hawai’i had the highest percentage of folks who could read and write. Not only were they able to write, many in both Hawaiian and English, which was a second language, but when they wrote, they continued to maintain the poetry and beauty of their native tongue, something we have lost and must retrieve. Our people became prolific writers, witnessed by the numerous Hawaiian language newspapers that were published. In fact, there exists much meterial and informaItion in the form of these newspapers that still need to be translated. I recall my grandmother, Mary Kawena Puku’i, saying she would have to live several more lifetimes in order to translate all the Hawaiian newspapers stored at the archives and /Bishop Museum, where she worked for many years. Alu Like’s Hawaiian Language Newspaper Project’s collection consists of approximately 120,000 newspages taken from 100 separate periodicals published between 1834 and 1948. These pages, however, contain many more words than today’s newspapers. A page today characteristically has 2,500 words, whereas a Hawaiian newspaper page may contain 6,600 words. I would like to share a family kanikau as am example of the beauty of the poetry of our language and the skill that our people possessed. Compare this with today’s obituaries that, basically, list name, birth/death dates and survivors. The following was written by Akoni Kawa‘a for his wife, Mary Rebecca Pu‘uheana, who was my grandmother’s aunt. They were foster parents of my grandmother, Kawena Pūku‘i, as she was raised by her maternal grandmother, Nali‘ipo‘aimoku, who the Kawa‘a’s lived with. The Hawaiian text is presented in its original form. Diacritical marks were not necessary because our people knew their language well. My aunt/foster mother, Patience Namaka Bacon, still writes in Hawaiian without the use of these helpers because she doesn’t need them. I very much appreciate the wonderful poetry and descriptiveness of our language and the great skill and understanding of our forbears in the weaving of their compositions and I hope that sharing this with others will foster a new appreciation for the talents of our people. L. La‘akea Suganuma, ʻŌlohe KA NUPEPA KUOKOA DECEMBER 11, 1903 Mr. Lunahooponopono, Aloha oe, Ma ka home pumehana o ko maua mau pokii aloha Mr. and Mrs. Mikalemi ma Aiea, Ewa, Oahu nei, a ma ka wehena o ke alaula o ka wanaao hora 4 of ka Poalima, Nov. 20 iho nei, aia hoi, ma ka palanehe luaole, me he malu ana la o ke ao polohiwa ia ka onohi o ka la, ua oili mai la he elele ike ole ia me ka upena o ka make ma kona lima, a hoohei ae la I ka hanu hope loa o kuu Mrs. Beke Puuhena, a kaili aku la i ke ala koula a Kane, a ahu iho la na pua wahawaha i Wailua, he kaa huila ole, he kino lepo, he hale naha e ku wala ana, ua helelei kona mau paia. Ua hanauia oia ma Kaunamano, Naalehu, Kau, Hawaii, I ka A.D. 1859, i ka malama o Augate ma ka puhaka mai o Mr. Kanakaole ame Mrs. Poai. Ua piha iaia na makahiki 44 ma keia ao inea a hele wale aku la no. Ua hoohuila maua me ka berita o ka maree ma Naalehu, Kau, Hawaii I ka A.Dd. 1897, e ka Hon. J.W. Waipuilani. He makuahine aloha no ka home, he puuwai waipahe no na makamaka me na hoaloha. Nolaila, e na kini o maua mai ka la hiki a ka la kau, kona mau pokii, ua moe a ua moku a ua pio ke kukui o ka hale o kuu hoa hoomanawanui o nei ao mauleule, ua moku ke kaula gula o kuu lei diamana, ua moe aku la I ka moe kau moe hooilo no ka wa mau loa. A nolaila, i ou mau kini apau o ke one kuilima o Ewa nei, ne makamaka ame na hoaloha, e oluolu e lawe aku i kou hoomaikai palena ole no ko oukou ae oluolu mai e u pu me au, a moe wale aku la no ma ka ilina o ko makou mau makua i hala e aku ma ke awakea o ka poaono, November 21. Aka, na ke Akua no i haawi mai a nana no i iawe aku, e hoomaikai ia kona inoa. O wau iho no me ka ehaeha, Akoni Kawaa Aiea, Ewa, Oahu, November 23, 1903

****

Greetings to you, Mr. Editor, In the loving home of our beloved younger sibling, Mr. and Mrs. Ed B. Mikalemi, in Aiea, Ewa, Oahu and at the opening of the flaming path of dawn at the hour of 4 a.m., Friday, November 20, behold with incomparable quiet like peace, the dark light in the eye of the sun from which appeared an unseen messenger with the net of death in his hands to snare the very last breatgh of my Mrs. Beke Puuheana and snatch it on the red pathway of Kane, heaped up with the flower of sorrow at Wailua, a wheeless carriage, an earthly remain, a house shattered, just barely standing with its wall fallen forever. She was born in Kaunamano, Naalehu, Kau, Hawaii in the year 1859 in the month of August, from the loins of Mr. Kanakaole and Mrs. Poai. She had reached 44 years of age in this world of hardship and suffering until her departure. We were joined in holy matrimony in Naalehu, Kau, Hawaii in the year 1897, by the Honorable J.W. Waipuilani. She was a loving mother for the home with a courteous and polite heart for the close friends and loved ones. Therefore, to our relatives from the rising of the sun to the setting of the sun, your younger sibling sleeps; the light of the house of my patient companion is extinguished; the golden thread of my diamond lei is cut; she sleeps the summers and winters forever. And therefore, to all my relatives joining arms in the sands of Ewa, the close friends and beloved companions, please take my unbound blessing for your kindness to weep together with me and to remain at the grave site of our parent who has gone, at noon on Saturday, November 21st. But it is for the Lord to give and for him to take. Blessed is his name. I remain grieving, Akoni Kawaa Aiea, Ewa, Oahu, November 23, 1903

**********************************************************

Another kind of respect was prevalent in those times and still exists with most people. However, there are too many today that do not possess any awareness of this. It is respect for the property of others. Doors were never locked and there was no fear of homes being broken into or one’s goods and possessions being stolen. Everyone knew that taking something that belonged to someone else would, without a doubt, cause problems for the offender.

If Po‘ai and Kawena were to be gone for an extended period, Po‘ai would just close the door, sit on the lowest step with her mo‘opuna next to her and ask Jehovah, her ancestral gods and ‘aumakua to keep watch over Hale Ola and her property “from north to south, east to west, top to bottom and inside and out. Leaving everything in their care, grandmother and mo‘opuna would set off to wherever they were going. While visiting Kawena’s parents once, a heavy rainfall prevented Po‘ai and Kawena from returning home, so they spent the night in Na‘alehu. When they returned home, they found some people at their home who got caught in the rain and sought shelter. Although they could have left early that morning, they decided to wait until the occupants returned so they might thank them and let them know what happened. They had not touched the sleeping mats and surmised, because of the little containers hanging from the rafters, that there was a child and didn’t touch her things. Not carrying any food, the ate what they found. Po‘ai asked them to spend another night so they could depart in the cool of the early morning, which they did. Once on their travels, Kawena became thirsty, so Po‘ai went to the next home but no one was there. She asked the unseen guardians if she could take some water for the child and thanked them when they left. Po‘ai later ran into the home owners and explained what happened. Makai of the gate to Hale Ola was a large stone with a flat surface, big enough for two to sit. It was an ancient ‘o‘io‘ina, or resting place for travelers going from Na‘alehu to Pu‘u-makani. Whenever Po‘ai heard one or more resting there she would always, after exchanging greetings, invite them in to have something to eat, whatever they had and, no matter how much or litttle there was, the best was always offered to the guest(s). That was the way of life….hospitality, sharing, kindness to strangers.

******

THE FAMILY HAKA -Kawena also learned about and experienced the work of the haka, the family trance medium. There was a time when every family had a haka. A haka was someone who an ‘aumakua (family guardian), ‘unihipili (kept spirit of a deceased person), kupua (demigod; supernatural spirit) or even akua (god,godess) would speak through and address the family that the haka and spirit belonged to. The haka provided a means for those in the spirit realm to communicate with those in the physical realm. The spirit would perch on the shoulder of the haka and take control of the haka’s body and speech, allowing the spirit to speak to those who were present. A haka was also called a waha-‘olelo (speaking mouth).

Kawena was told by Po‘ai to be quiet and observe what transpired in these sessions. The haka that Kawena watched was a close relative of her mother. Kawena noticed that the haka did not know what happened from the point where the spirit took over until it left. During one session, Kawena was so tired that she fell asleep in the lap of the haka.

There was a procedure that had to be followed. The haka had an assistant, referred to as a kanaka pule or kanaka lawelawe. He or she would set up the area using a mat or cloth, the color depending upon which spirit would come. La‘i or ti leaves, of a special variety only, were place in a pattern. ‘Awa was prepared and the area and everything used would be purified by pikai (the sprinkling of water with pa’akai (salt) and sometimes ‘olena (tumeric) mixed in called wai-huikala. This attendant would make sure the haka had the right clothing, say the prayers and carry out orders and had to be a man, a woman past menopause or a pre-adolescent girl. Both haka and the kanaka lawelawe lived under strict kapu. Kawena recalled that there was some discussion about her being trained to be a haka, but it never came to pass.

Kawena’s grand uncle, John Kai’a Baker, told her a story about his experience with a haka, a relative, who was visiting Akoni Kawa‘a’s sister in Aiea, O‘ahu. He was a poiceman in Honolulu at the time and wanted to ask about his chances of winning a marksmanship competition the following day. On his way to the house, he walked along the bank of a taro patch. Looking down, he spotted some shrimps, bent over, caught a few and put them in his pocket. When he reached the house, the haka was already possessed by the spirit of a child. To test him, he asked the child if he could tall him exactly what he had in his pocket. The child laughed and said, “You have a quarter and some shrimp. I passed you as you bent over to catch them in the taro patch.” That was exactly right and so he asked if he would win the shooting match the next day. He was told he would win if he stayed away from drinking alcohol. He drank anyway and came in second.

- * * * * * * * * *

PO‛AI’S HOME, Hale Ola, was originally built at Waikapuna, near Poninau by Po’ai’s mother, Keli’ipa’ahana, who kept herds of goats at Waikapuna and Ha’ena in the 1860’s, when their hides were exported. Saving her money carefully, Keli’ipa’ahana was able to build the very nice frame house. After both, Keli’ipa’ahana and her daughter, Po’ai, became widows, they moved the home to Haniumalu. This land had been in the family for generations. It was their farming place; a place to grow sweet potatoes, which was the main staple for the people of that area. Taro was grown at Waiohinu, Waikalonā and other upland places in small amounts, but in that area, sweet potato was the main food. Po’ai had a large patch of sweet potato both in front and back of the house. She also grew watermelons, tomatoes, green onions, chili pepper and pumpkins. Po’ai also had fruit-bearing trees such as papaya, avocado, guava, loquat and rose apple. There were honeysuckle, chrysanthemums, ha’iku, geraniums, roses maile haole and verbenas that also grew in her garden. She always grew more than what was needed by her household, as well as those of her daughters, so she could share with ‘ohana (famiy) that lived on the shores and who frequently came to visit, with dried or fresh seafoods and fish. The old Hawaiian way of subsistence was still in effect. ‘Ohana from the uplands would share what they grew with shore-dwelling kinsmen who would share their fish and other foods they had. This system of sharing was the Hawaiian way of life. Po’ai liked to spend a part of summers on her favorite beaches at Pa’ula and Waikapuna where she would fish and gather salt. She always took sacks of sweet potatoes with her to share. Of course, little Kawena would be with her.

On the acreage of Hale Ola was an area for growing weeds. Those weeds were medicine and attended to only by Po’ai who was trained as a kahuna la’au lapa’au (medicinal expert) and pale keiki (midwife). In this patch grew medicinal weeds such as koali, pukala, ‘ihi, uhaloa, kukaepua’a, laukahi and others. There was a noni tree and popo’ulu and lele bananas to treat ailments called ‘ea and pa’ao’ao. If other types of mountain plants were needed, such as lehua, mamaki, pala, etc., Po’ai rode on horseback to the forests back of Waiohinu and Kahuku. If other plants were needed, there was Hono-Kane gulch. Medicinal plants and herbs were always picked at particular times and with the proper hand, accompanied by prayers. Prayers were also important when administering medicines. Wherever Po’ai went, her grandchild, Kawena, went too. Just below the house was an old dry stream bed that once was filled with flowing water. On its banks grew ferns and various upland plants. An old story said that the goddess, Hina, had once rested by this stream under a shelter she made of coconut leaves, giving the place the name Haniumalu (coconut leaf shelter) After water was diverted by the plantation, the stream dried up. Some then called this place Kapaliwai’ole (The hill with no water), but those who lived there and loved the area used the old name, Hāniumalu. A three foot high stone wall surrounded the four acres that Hale Ola stood on. A sugar cane field in front of the house extended almost to the main road leading down to Honu’apo or up to Waiohinu. Water for the house, cooking or washing clothes came from a flume that crossed the front of the property, within its boundaries and was available for use from 4 PM to 8 AM. Hale Ola consisted of three rooms in a row, with a wide lanai from end to end. One of the rooms was Po’ai’s bedroom which was furnished with a large koa bed, covered by a quilt made by Po’ai. The pillow case, edged with crocheted lace, was starched. The floor was covered with a lauhala mat. There was also a koa dresser and trunk. A mosquito net, hanging from the ceiling, was neatly tied back with a ribbon. Po’ai rarely ever slept in her bed. Her daughter, Mary Rebecca Pu’uheana’s room was similarly furnished by also had a sewing machine, with which she skillfully made holokus and mu’umu’us for her mother and sisters. There was no furniture in the parlor, just a table in the corner where Po’ai kept her bible. No one was allowed to sit or stand with their backs facing her bible, nor could anyone sleep with their feet facing it. The floor was covered with a lauhala mat. There were a few family pictures on the wall, and also a Japanese picture scroll. This was the sleeping room. Everyone had their own sleeping mat and blanket which were aired out every morning and rolled up for the next night’s use. The house was built high enough to walk under and provided space for storing saddles, wood and other items, as well as a workroom for Po‘ai, which was Kawena’s favorite room. The ground was covered with small stones, about twelve inches deep, so that dirt could not soil the room. On top of this layer of stones was a thick layer of dried banana leaves and ‘ilima branches. On top of this were three lauhala mats with decreasing mesh from bottom to top. Rolls of lauhala were stacked against the walls, up to the ceiling. Most of the rolls were of dried lauhala, gathered from the tree. This lauhala could only be worked on in the evening, on cool or rainy days. Heat would make the leaves brittle and difficult to work with. The others were of young leaves, carefully prepared by toasting over a fire. These were for making fine mats and were called lauhala ‘ōlala. Kawena’s father, Harry, persuaded his mother-in-law to add three more rooms to her house; a bedroom, a kitchen and a pantry. He bought her a new wood burning stove from the plantation store, which would be started with a little kerosene. It was a fine stove, something to show visitors, but was never used by Po‘ai. A customary feast was held at the completion of the addition, the same as when a new house is dedicated. Po‘ai preferred cooking outdoors as she always had, A shallow hole was lined with stones, except for one side. Two iron bars were laid across to keep the pots over the fire. The iron pots would take much scrubbing to clean the smoke-blackened pots.

Kawena’s great grandmother, who built Hale Ola, Keli‘ipa‘ahana (The industrious chiefess), had a twin sister, Kalimakuhilani (The royal hand that points). They were both named for a Ka‘ū chiefesss and relative, Po‘oloku. She had a fiery temper and was always directing her people, pointing at work that needed to be done, but working right alongside them. One day, when digging holes and planting bananas in a long gulch, between Pakini and Kama‘oa , some men told her to sit and they would do the digging. They received a shower of stones from her, telling them to get to work at their own tasks. Because of her industrious nature, her people were always well fed and taken care of.

Keli‘ipa‘ahana was married to Kanakaokai aka Keli‘ikanaka‘oleoImakakoloa. He was a Maui born cousin of Boki who hated court life and left Maui. He preferred the simple life and went by Kanaka‘ole, dropping the Keli‘i and Imakakoloa parts of his name. They met in Puna, where she was visiting relatives. Their daughter, Po‘ai, was born in 1830, in Keahialaka, Puna, before they moved to Waikapuna, Ka‘ū. He was named for the chief, Imakakoloa who was named for a earlier chief, I-mai-ka-lani. Imaikalani was the blind chief of Ka‘ū well-known for his strength and prowess in battle. He destroyed many chiefs who went up against him, splitting them in half. ‘Umi-a-Liloa had been trying for many years to conquer Kaʻū and feared I-mai-ka-lani. Although blind, his secret was the ducks he trained to warn him of an approaching foe. He also had men around to hand him his weapons and tell him where the enemy was and the positioning of his foe’s weapons. Imaikalani only perished after his secret was discovered. One of Umi-a-Liloa’s generals watched him until he learned the sources of Imaikalani’s strengths, then killed his ducks and his attendants. Only then was Imaikalani defeated. I-maka-koloa (I with the eyes of ducks) was a chief of Puna named for Imaikalani. He had led a rebellion against Ka-lani-‘ōpu‘u and had to flee for his life, hiding for a year while Kalani‘ōpu‘u’s men hunted for him. Historians said that he was found hiding and was sacrificed at the dedication of the heiau Halau-wailua, near Kama‘oa. This is the dedication where Kamehameha grabbed the body when his cousin Kiwala‘o was supposed to, which started the great rift between them.

However, the story whispered throughout Ka‘ū was that another, who looked like the chief, voluntarily took his place, after discussing this plan with his father, who directed Kalani’ōpu’u’s men to where his son was convincing them to release the real chief. Imakakoloa spent the rest of his life as a simple farmer. Po‘ai’s father was named for him, (Imakakoloa, the chief without servants). Kanaka‘ole died before Po‘ai was a year old, so mother with daughter moved back to Kama‘oa, Ka‘ū. About a year later, Keliipa‘ahana married Kanekuhia, a Lono priest, who loved and raised Po‘ai as his own. . Keli‘ipa‘ahana was the last in the family to be buried in Kilauea. Her daughter, Po‘ai, was the first of her generation to have a Christian burial. Keli‘ipaahana was a beautiful dancer and taught her daughter the chants and dances of Pele. She was also an expert midwife and passed that knowledge on to her daughter. Kanekuhia was a priest who was trained in the temple of Lono at Kealakekua, in Kona. This was where Captain Cook landed and was thought to be Lono. He passed on to Po‘ai the lore of the priesthood of Lono. When Po‘ai was fifteen, her cousin, Kuku‘ena-i-ka-ahi-ho‘omau-honua, aka Pamaho‘a, who was terminally ill, asked Po‘ai to marry her husband so she would know her children would be cared for. She had given birth to seven, but only two survived. Po‘ai agreed and after Pamaho‘a passed, she married Ke-li‘i-kanaka-‘ole-o-Haililani, who was forty. Po‘ai raised her cousin’s two children, Ka‘ia (k) and Kukuena Pamaho‘a (w ), who were very young when their mother died. She and Kanaka‘ole had 15 children (12 daughters and 3 sons). One son died in infancy, another at twenty-two and one lived to old age but had no children. Of the girls, four have descendents today. As far as Po‘ai was concerned, however, they were all her children and would be furious at anyone who mentioned a “step” relationship or “half” sibling relationship. Keli‘ikanaka‘ole’s father, Mokila, was a cousin, constant companion and head kahuna kalai-wa‘a (canoe making expert) for the Ka‘ū chief, Haililani aka Lilikalani (an ancestor of Cy Bridges, board member of the Mary Kawena Pūku‘i Cultural Preservation Society) of Kama‘oa, Ka‘ū. Mokila’s wife, Kuakāhela, was the namesake for he who returned to Ka‘ū from Kawaihae, wailing about the death of the Ka‘ū ali‘i, Keōua-kū-‘ahu-‘ula and the Ka‘ū chiefs and warriors slaughtered by Kamehameha, who invited them to a peace meeting, for which he said to come unarmed. Upon arrival, they were attacked by Kamehameha’s army. The popular version of Keōua’s death claimed that Ke’eaumoku speared Keoua as he stepped off of his canoe. Another version was that Ke’eaumoku grabbed and drowned Keōua when his canoe landed on the beach. Those stories never happened.

Though unarmed and in canoes, the Ka‘ū warriors fought for hours, catching spears and stones and returning them, killing many of Kamehameha’s warriors. Keōua stood on one bow of his double-hull canoe and his general, Ka’ie’iea stood on the other and fought from morning to afternoon, until the great Ka‘u ali‘i was felled by a sling stone after telling Ka’ie’iea that his arms were weary. Only by treachery could Kamehameha win over the fierce Ka‘ū fighters.

Mokila and Kuakāhela had four sons, each named after the chief, Haililani with inoa kuamuamu. When Mokila heard an insult directed at Haililani, he would name his sons thusly: When someone said Haililani had no servants, his son was named Ke-li‘i-kanaka-‘ole-o-Haililani (Haililani, the chief without servants). This son was said to be over seven feet tall. The next was Ke-li‘i-kahakā-o-Haililani (Haililani, the insignificant chief). Then Ke-li‘i-kipi-o-Haililani (Haililani the traitorous chief) and Ke-li‘i-pio-o-Haililani (Haililani, the captive chief). When the eldest died, the second son took his name. He was born in 1805 and Po‘ai became his second wife. Their marriage was not of love, but Po‘ai was chosen because of her kinship to Kanakʻole and they having the same priestly background. He was a noted kahuna la‘au lapa‘au and is mentioned, along with his foster brother, Keku‘a, in a book in the Bishop Museum in which Kalakaua made note of him. He was also a kahuna ho‘oulu i‘a (expert concerning fish habits). He imposed the setting and releasing of kapu regarding fishing for the area and was reputed to be a very good fisherman. At Wai-ka-puna stood a stone named Kanoa. It was here that Kanaka‘ole used to stand, praying with his ‘apu ʻawa (coconut cup for ‘awa) before him on the stone, which was used only to lay offerings upon, to free (hoʻonoa) the kapu he had imposed earlier in the year. After the kapu was freed, the first five days’ catch belonged to the chiefs, who maintained large households. The catch for the next three days belonged to the konohiki (headman of an ahupua’a land division) and the people fished freely thereafter. Many years before his passing, this practice ceased. After the death of Kamehameha, Ka‘ahumanu abolished the old kapu system, which included the strict conservation laws in effect for many centuries, keeping the people fed. All of the rules concerning effective land and ocean management and conservation collapsed. However, Kanaka‘ole continued his ways, fishing for his family and kinsmen and remembering his chiefs, with his catch.

In May 1940, Kawena presented “SONGS (MELES) OF OLD KA‘Ū, HAWAI‘I” at a meeting of the Anthropological Society of Hawai‘i, later printed in the Journal of American Folklore, July-September, 1949. The following chant, composed in about 1850 is about her grandfather, his younger brother and their cousin, fishing in the sea of Manāka‘a, Ka‘ū.

KA-LAWAI‘A-HŌLONA-I-KE-KAI-O-MANĀKA‘A

The Unskilled FIisherman At The Sea Of Manāka‘a

Eō e Ka-lawai‘a-hōlona-i-ke-kai-o-Manāka‘a

Ku mai o Kanaka‘ole ka mea iāia ke uha‘i o ka ‘ulei,

E ho‘omakaukau kākou ‘oi kau ka lā i luna,

O waiwai ‘ole o Alakaihu-i-ke-Kupa‘ai,

O ke-kipi-o-Haililani ka i ke kaua ‘iako,

O Waiu, o Lumaheihei ka i ka‘a i ‘o,

Moehau‘una ka maka o ka i‘a,

Pupuhi kukui, ahuwale lalo, ‘ikea ka i’a a ka hōlona,

Kahea mai ua lawai‘a nui nei, “E ke keiki, pehea a’u?”

Pae a’e a uka, pākahi, pālua, pākolu,

Ku mai o Kapule ka mea iāia ke ka‘i o ka ‘aha,

O Huli-o-kamanomano ke ka‘ika‘i i na ipu,

O Ka-‘ai-‘uki ke kōmikōmi ma ka paia,

O Kalua-kapu-kane ‘ole‘ole,

Ku mai ka hikiwawe Keawehano,

Lohe aku la ka uka ma‘ulukua i ka i‘a a ka hōlona,

Ninau mai o Pamaho‘a ia Kanaka‘ole, “Ua hei ia ‘oukou ka i‘a?”

“Ae, ua hei ia mākou ka i‘a, ho‘okahi lau me ke ka‘au keu elua,”

Ku mai o Kahalikua-ka-manomano,

Ka hihipe‘a, ka ‘imi pono o na kaikua‘ana,

‘A‘ohe no he mamo lawai‘a; he mamo mahi‘ai,

I mahi i ka lā me ka ua,

Kuhihewa ua lawai‘a nui nei i o‘o ka lae i mino ka papālina,

Ke holo la i ke a makapouli o ku‘u ‘aina,

I ke kai o Ka-wai-uhu Uhu mai na keiki lawai‘a nui a Kaha‘i-moku, Ninau, “Pehea la ka i’a o Manāka‘a?”

Ho‘ole ua lawai‘a nui nei,

“‘A‘ohe i‘a, he i‘a na ka hōlona.”

‘A‘ohe no he lawai‘a nui i ‘ole ka ‘ai i ka pipipi i ka hulalilali,

Piha ka waha o ua lawai‘a nui nei.

O na inoa pākolu kēia o na makua o‘u i hea ai i ku‘u keiki,

O ka lawai‘a hōlona kona, o ka inoa ko ia nei a.

O Huli he makua, e o a.

Answer, O The unskilled fishermen at the sea of Manāka‘a,

Kanaka‘ole, who held the native rosewood rod, stands forth,

(Saying), Make ready while the sun is still above.

Lest Alakaihu-i-ke-Kupa’ai be without (fish).

Ke-kipi-o-Haililani was at the place where the outrigger boom joined

the canoe.

Waiu and Lumaheihei sat beyond him.

The eyes of the fish were blinded (by the light).

The kukui nuts were blown into the water, (on) the sea floor could be seen the fish of the unskilled ones.

The great fisherman called out, “My boy, how about me?”

Once, twice, thrice they went ashore.

Kapule, who was in charge of the guide line stood forth,

Huli-o-ka-manomano was in charge of the containers,

Ka’aiuki patted along the sides (of the net)

(While) Kalua-kapu-kane talked incessantly,

The quick one, Keawe-hano, stood forth,

For the news of the fish of the unskilled ones had reached inland. Pamaho‘a asked Kanaka‘ole, “Did you catch any fish?”

“Yes, we have caught four hundred and eighty.”

Kahalikua-ka-manomano stood forth,

She who was interested in the affairs of her elder sisters,|

We are not the descendants of fishermen but of farmers,

That farmed in the sun and the rain.

The great fisherman with strong forehead and wrinkled cheeks was mistaken

And ran over the blackened lava beds of my land

To the sea of Ka-wai-uhu.

The sons of the great fisherman, Kaha‘i-moku,

Asked,”How is the fish of Manāka‘a?”

The great fisherman denied that there was fish.

“There is none, except for the unskilled.”

No great fisherman had even gone without eating the pipipi shell fish of the shiny lava rocks,

These have filled the mouth of the great fisherman.

The name given to the child was for her three fathers (father and uncles).

They were the unskilled fishermen, but the name is hers,

Huli was her mother,

O answer to the name chant.

Kanaka’ole (Ke-li’i-kanaka-‘ole-o-Haililani) was Kawena Pūku‘i’s grandfather, who sired her mother, Mary Pa‘ahana Kanaka‘ole. Ke-kipi-o-Haililani (Ke-li‘i-kipi-o-Haililani) was his younger brother and Kawelu was their cousin. Keawe-hano was a noted fisherman and is referred to as “the quick one.” The three men, from Waikapuna, Ka’ū, began to fish in the sea of Manāka‘a (at the eastern end of Waikapuna and outside of Kawaluhu.) Keawe-hano made fun of them and called them the unskilled fishermen of Manāka‘a. Kanaka‘ole, who was a noted kahuna la‘au lapa‘au (medicinal kahuna) and kahuna ho‘oului‘a (expert on fish habits), began to offer prayers to a female ‘aumakua who lived in the sea. It was said that she answered his prayers by giving him quantities of fish (480) which he caught for his chief, Alakaihu-i-ke-Kupa‘ai. When the first great haul of fish was caught at Manāka’a, Keawe-hano forgot his unkind words and in his excitement, ran to help so that he might be given some. Pamaho‘a was Kanaka‘ole’s first wife. When she knew she was going to die, she asked her cousin, Nali‘ipo‘aimoku, to marry her husband after her death so she knew her children would be taken care of. Po‘ai did so and had fifteen children with Kanaka‘ole. She was Kawena’s grandmother who raised her from infancy. Not long after this event, Huli-o-ka-manomano, the wife of one of the fishermen, Kawelu, gave birth to a little girl. This was her name chant and she was named Kalawai‘ahōlonaikekaiamanāka’a. Years later, after this little girl had grown up and married, she gave birth to a stillborn baby. Kanaka‘ole placed the child in a large calabash, held the calabash up to catch the warmth of the sun, and prayed that she would live. The baby stirred and cried and it was Kanaka‘ole who named her, “Hanau-maka-o-Kalani” (Kalani who was born from an eye), for a shark ‘aumakua who was born from his mother’s eye.

******

Kaʻū was somewhat isolated and therefore, insulated from the politics, Christian missionary demands, foreign influences and rapid changes taking place in Honolulu. Her grandmother had adopted Mormonism in 1871, but she never abandoned the old ways and would rise early and give voice to ancient chants, so old that they were said to be composed by the Gods themselves. She would chant in praise of her beloved Pele, the Fire Goddess, Akua to all, but also aumakua to the fire clan of Kaʻū. .When Catholics and Congregationalists began activity in Ka‘ū, Poūai and her mother assisted them with no favoritism or preference. Po‘ai would say, “For God, one mustn’t grumble.” Besides her Holy Bible, Po‘ai had rosaries, medals a catechism and a Hoku Ao Nani hymnal; all sacred items to her. Her son, Ke-li‘i-kipi-o-Haililani, was taught by Father Kelekino (Celestino) and became and remained a Catholic. In late 1869 and early 1870’s, Mormons became active in Ka‘ū, Po‘ai and many of her ‘ohana joined. Her cousin, Kahoali‘i, was the leader of the Waiohinu group; Joseph ‘Ili, husband of her granddaughter, Kulu-wai-maka, headed the Na‘alehu group; a niece, Lokinihama, gave a portion of her land at Nalua for the building of a church; her son-in-law, Akoni and his wife, Mary Rebecca Pu‘uheana, a cousin Na-ono-‘aina and his wife, Na-iwi-elua, a relative, and many others of her ‘ohana became Mormons. Po‘ai attended church regularly, occupying a front row seat, closest to the pulpit. Po‘ai and Kawena would walk from her home in Hāniumalu to Nalua faithfully, even when age and rheumatism hampered her movements. She and her mo‘opuna would walk, rest, walk, rest, Po‘ai with her cane, to and from Nalua. Kawena would often get bored and fall asleep, or slyly make faces at the other children in the back.

Kawena and her grandmother were visiting her mother at her parents’ house when she saw a Japanese girl about her age, the daughter of the gardener. The girl had a “rice bowl” haircut, straight bangs across her forehead and short all around. Kawena’s hair was carefully brushed by her foster mother and aunt, Mary Rebecca Pu‘uheana and was in two long braids. Kawena got ahold of a scissors, sat before a mirror and began to give herself a haircut, attempting to copy what she saw on the Japanese girl. The more she cut, the worse it got. Her mother and grandmother gasped when they discovered her. It was so bad that they had to call the barber to come and he had to cut it all close to the scalp, just to even it out. Po‘ai looked at her granddaughter and proclaimed, “This is the manewanewa, the mourning of the dead, a sign of death.”

As Po‘ai predicted, death came swiftly. Kawena’s aunt, Annie Kukuena, the gayest of Po‘ai’s daughters had been at an all night party at the Hawaiian camp in Na‘alehu. She and a friend walked over to her sister, Mary Pa‘ahana’s, house where Kawena and Po’ai were visiting with her mother and having breakfast. Annie Kukuena was telling happy stories about the party they had attended and laughing when she picked up Kawena and kept repeating, “Our baby….our pretty baby” as she walked to a bedroom to lie down. With a gasp, she fell to the floor with Kawena in her arms and expired. Dr. Thompson was called and pronounced her dead. Annie Kukuena was taken to Hāniumalu where relatives from all over the district came to wail over the loss. It was customary to wear black and Po‘ai had nothing to wear, so her daughters hastily shopped and sewed two holoku for her in a few hours. Annie was laid to rest next to Kawena’s older sister, Mary Binning.

Soon after, Dr. Thompson was called to the house again. Po‘ai had a stroke and her daughters lay her in her koa bed to rest. Kawena was told to be quiet and was kept away from Po‘ai’s bedroom. A few days later, Po‘ai somehow indicated to her daughters that she wanted to see her mo‘opuna. Kawena was taken to her grandmother and was shocked to see how her mouth was twisted. She kissed Po‘ai’s cheek before she was led out of the room. It was exactly one week after Annie Kukuena had died when Po‘ai passed away. Mary Rebecca Pu‘uheana, being the eldest, had to prepare her mother for burial. Kawena’s mother, Mary Pa‘ahana assisted. Po‘ai was bathed in her bed, salt in think cloth was placed on her navel and she was dressed in her best holoku. She was placed on boards supported by saw horses, feet towards the front door and a silver dollar placed on both eyelids so the eyes would not open, which meant another would follow i death. A few leis, made from the flowers in her garden, were placed on her. Relatives and friends came from all over, bringing food for all to share. As was custom, her daughters faced the front door so they could see who approached. When recognized, a wail from one of them would welcome the mourners, telling of the loss of their mother.

Those approaching would wail in return, telling of the relationship and how the deceased would be missed. Perhaps mentioning stories of times shared together. Between arrivals, people would talk, sing the deceased’s favorite songs, or dance a favorite hula. Three old women, who Kawena had never seen before, approached. They were from Moa’ula in the uplands. They laid down a mat and kneeled in a row. They wailed and swayed in unison, beating on their chests with clenched fists, clasping their hands behind their necks and flinging them up towards the sky while wailing, “Auwe ku’u kaikua’ana!” (Alas, my older sister!) Po‘ai was an only child, so these were junior cousins. As Kawena watched them, held in the arms of her foster father, Papa Akoni, she asked what they were doing. “That is the pa‘i-a-uma,” he said. Kawena never saw that again.

Po‘ai was laid to rest next to her daughter, Annie Kukuena, and it wasn’t until she saw the coffin being lowered into the ground that little Kawena realized she would never see her beloved grandmother again. She sobbed for the first time since her grandmother was stricken. After the coffin was lowered, personal items were added; her kukui nut lei, her clothing, favorite hats and even her hand sewing machine. It was an ancient custom to ho’omoepu, to put personal items with the deceased. A lock of Kawena’s hair was put in Po‘ai’s coffin so she could take a part of her mo‘opuna with her and not look back. The only thing that was forgotten was her favorite poi pounder. It was given to Kawena who passed it on to her grandson, La‘akea, who she cared for in infancy like her grandmother did her.

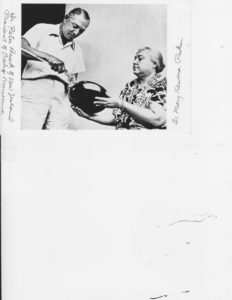

NALI’IPO’AIMOKU’S favorite pōhaku ku‘i ‘ai (poi pounder), the one with which Kawena learned how to pound poi as a little girl.

pōhaku ku‘i ‘ai (poi pounder), the one with which Kawena learned how to pound poi as a little girl.